A blood stem cell transplant may halt disease progression in certain adults with cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a study reports.

The study, “Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with myeloablative conditioning for adult cerebral X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy,” was published in The Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease.

Childhood cerebral ALD, a disease that affects mainly males, is the most common form of ALD, characterized by an inflammatory process that destroys myelin — the protective layer around nerve cells’ axons. This leads to progressive loss of cognitive and neurological functions including communication and voluntary movement, blindness, and incontinence.

Adult cerebral ALD is relatively rare. Patients with the disease experience rapid neurodegeneration, and develop severe disability within a short period after disease onset.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is the only way of stopping disease progression in boys with cerebral ALD. HSCT is based on the transplant of hematopoietic stem cells — cells that can form all types of blood cells in the body — from a genetically similar donor (allogeneic), usually a close relative of the patient.

However, few studies have reported on HSCT’s efficacy in adults with cerebral ALD.

Now, researchers in Germany analyzed data from a group of 15 adult males with cerebral ALD who underwent HSCT at a transplant center in Berlin.

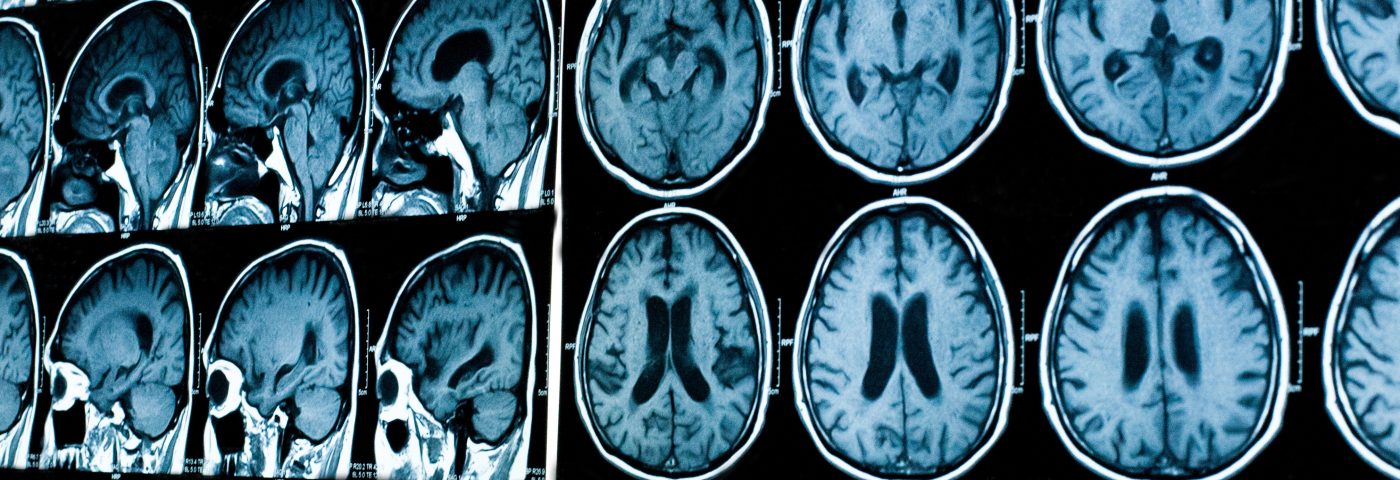

Patients’ clinical status was evaluated using the Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS; the most widely accepted clinical disability scale), the adult ALD clinical score (AACS), and by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to quantify the level of myelin loss.

Before the transplant, four patients had mild symptoms (EDSS less than 4), and six patients had advanced nerve degeneration (EDSS equal to or greater than 6). Moderate cerebral dysfunction (cerebral domain in AACS greater than 3 points) was seen in eight patients. The median MRI Loes score (a way to quantify the severity of white brain matter loss) was 7 points — the Loes score ranges between 0 and 34, with higher scores meaning more severe loss.

All patients received myeloablative chemotherapy before HSCT to destroy the diseased blood-forming cells in the bone marrow, and increase the success of the transplant. To decrease the chance of the immune system attacking the transplant — a condition called graft-versus-host disease — patients were given preventive treatment with anti-thymocyte globulin and cyclosporine.

Four patients died within the first year after HSCT due to an infection (three patients) or disease progression triggered by infection (one patient).

The other 11 patients remained alive after a follow-up of approximately 56 months.

Two years after transplant, nine of the 11 surviving patients had stable cognitive function, as shown by no changes in AACS relative to their scores before the transplant; five patients had a stable motor function (no changes in motor domain of AACS).

Also, after HSCT, the very long chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) plasma levels — the conventional diagnostic marker for ALD — were reduced.

Furthermore, researchers saw that patients with no or mild cerebral symptoms before the transplant were those with better outcomes — patients with an EDSS less than 4 prior to transplant survived without an event. In contrast, no patient with major neurological symptoms survived without cognitive deterioration.

Overall, based on the results, the team concluded that “allogeneic HSCT appears to be a suitable treatment option for carefully selected [adult cerebral ALD] patients when transplanted from matched donors after [chemotherapy].”

The team suggested that patients with lower EDSS scores and without advanced cognitive deficits might benefit the most from HSCT.